Michael Story: A Landlocked Painter Rediscovers The Low Country

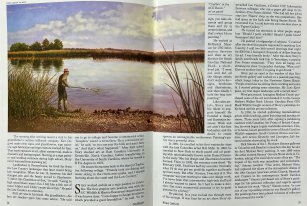

Wetland Respite — The moon rises between palmettos as hastening night draws heat from the marsh. Advancing Sky, Beaufort — Clouds reflected in estuarine waters advance eastward over the tree line, not once, but twice. Autumn Tide — Spartina gold as bullion bows beneath a wind heavy with the fertile smell of salt marshes. The paintings transport viewers to South Carolina's 32nd and 33rd latitudes, The Lowcountry, a place Michael Story speaks of with studied reverence. "I love exploring the interconnections where land and water meet. Water, real and imagined, exudes a calm that seems magical. Interpretations of clouds, trees, vegetation and grasses often find a place in my paintings, but their reflected colors and shapes in the surrounding waters interest me the most."

The words are surprising considering Michael Story did not like the Lowcountry at first.

Michael Story, born in Beloit, Wisconsin, moved to Pennsylvania at an early age. Each August, his family made the 827-mile drive back to Beloit, from Downingtown, a town much like the setting for a John Mellencamp song, a mid-America working town near Amish Country. For Michael, this annual drive would prove pivotal, a passage to art itself.

"We always visited my mom's dad (Ken Osgood)," said Michael. "He was a professional artist, and I couldn't wait to see him. He'd do a portrait of my sister and me as soon as we got there."

The morning after arriving meant a visit to his grandfather's sign shop. "He made neon signs, so he had glassblowers and different people working for him," said Michael. That early exposure to art, albeit commercial, made a dramatic and lasting impact. Starting as a sign painter and working summers during high school, Michael never wavered from pursuing art.

Landlocked in Pennsylvania, Michael lived far from the Lowcountry landscapes that would later bring him recognition. When he was 15, however, his dad changed jobs and the family moved to Charleston. "I didn't like Charleston at first," Michael said. "Going to high school there wasn't fun. I felt like a fish out of water. I didn't surf. I didn't water ski or fish." Michael paid the Lowcountry no attention.

Landlocked in Pennsylvania, Michael lived far from the Lowcountry landscapes that would later bring him recognition. When he was 15, however, his dad changed jobs and the family moved to Charleston. "I didn't like Charleston at first," Michael said. "Going to high school there wasn't fun. I felt like a fish out of water. I didn't surf. I didn't water ski or fish." Michael paid the Lowcountry no attention.

Still, art was in his blood. His grandfather - his first art teacher - gave him some advice. "he told me to go to college and become a commercial artist. Graphics wasn't a term then. 'Be a commercial artist,' he said, 'so you can pay the bills and paint later on.' And that's what happened." After high school, Michael studied art at East Carolina before transferring to the University of South Carolina, where he earned a B.F.A. degree. Michael traces his success back to the days in Charleston following college. "Friends took me fishing and water skiing in the rivers and creeks, and I started learning about the coast and the Lowcountry."

The Leap to Art

Michael worked a while as a sign painter. His first graphic artist position was with the SC Wildlife Department. "I was happy to design brochures, which provided a good foundation," Michael said. "In design, you take elements and group them and try to create interest, and that's what I do in painting." He worked at McKissick Museum for USC Information Services and then worked as the art director for SCN Bank, a short-lived job. "I went out and did all the things artists don't want to do - signs, brochures, and illustrations, and then finally I took the leap into painting."

Like other artists and writers, Michael used his talent to support himself. He founded a design and illustration business. Work and art aren't the best bedmates, and the desire to create spawns an unimaginable restlessness. Painting's purity was a powerful draw.

Like other artists and writers, Michael used his talent to support himself. He founded a design and illustration business. Work and art aren't the best bedmates, and the desire to create spawns an unimaginable restlessness. Painting's purity was a powerful draw.

In 1981, Michael enrolled in his first watercolor class with the late South Carolina artist Robert Mills. In 1982, he traveled to New York to study pastel and oil painting with internationally known artist Daniel Greene. Throughout the 80s into the early 90s, Michael's design and illustration business boomed. Then, in 1992, the economy nosedived.

"By February 1993, I had lost half my accounts. Normally what I'd do was get my portfolio together and hustle up more work. But after 18 years, I was sick of it. The computer was just starting to take over design work. I've never been that interested in high-tech stuff, and I always wanted to paint. So, I had to make a decision: get more commercial accounts or try to paint pictures for a living."

Michael painted. In a year, he had run through most of his savings. It was time for an art show. Michael approached Lee Cauthren, who ran a paper gift shop in Five Points.

"I had worked with Lee at USC Information Services, and she had left her job to start her 'Papers' shop, so she was sympathetic. She had space on the backside facing Santee Street. We renovated it so I could have my own one-man show in the 'Papers Gallery.'"

Michael turned his attention to what people might buy. "Should I paint wildlife? Should I paint boats? Seascapes? Still lifes?"

He painted a hodgepodge of subjects. "I realized after the show that people responded to anything Lowcountry. I sold two little pencil drawings that night for $300 but I had spent thousands of dollars framing my art. I was literally broke. After the show, my family, friends, and I went into Yesterdays. They were all happy, celebrating my show. I remember thinking 'what now. Give me another beer; I'm going to get drunk.'"

He painted a hodgepodge of subjects. "I realized after the show that people responded to anything Lowcountry. I sold two little pencil drawings that night for $300 but I had spent thousands of dollars framing my art. I was literally broke. After the show, my family, friends, and I went into Yesterdays. They were all happy, celebrating my show. I remember thinking 'what now. Give me another beer; I'm going to get drunk.'"

Michael put an easel in the window of that Santee Street gallery and worked on a peacock painting, which hangs today in the Newberry Opera House. ''People would see me sitting there working and come in. I started getting some attention. My Lone Egret piece, my first major landscape, sold a month later."

Word got around. Lexington Medical Center purchased some of his art and donated it to the George Herbert Walker Bush Library. Carolina First CEO, Mack Whittle, bought several of Michael's paintings for his bank and his private collection.

In 1994, Michael began to publish limited-edition prints while teaching, guest lecturing, and jurying art shows. Three years later, after signing a publishing contract with Canadian Art Prints of British Columbia, his work began to gain worldwide attention. Closer to home, his art graced the cover of South Carolina Wildlife. South Carolina Homes and Gardens, Arts Across Kentucky, and Lexington Life published feature articles showcasing his work.

Rick Simons of the I. Pinckney Simons Gallery recalls full well the day he saw a Michael Story painting. "In 1995, an artist not known to me came into our Gervais Street gallery and asked if he could show me some of his paintings. The impact of his work was immediate and overwhelming. This artist, Michael Story had captured the allure of the atmospheric drama of the 19th Century American artists Church, Bierstadt and Cropsey in his contemporary South Carolina landscapes." Simons purchased one of Michael's paintings for his personal collection and eagerly agreed to feature his work in the I. Pinckney Simons Gallery. "Story", said Simons, "is now one of our top selling artists in our Beaufort gallery. His paintings have been placed in homes of collectors from around the world."

Approximately 300 works of art later, you could say Michael made the leap to art, and he did, but adversity of the worst sort knocked on his door. He lost the ability to paint.

A Setback

In the summer of 2007, Meniere's disease struck Michael. By December, he had surgery, but the surgery went bad. "I had a spinal fluid leak, and I was ten times worse than before. I had episodes of the room spinning. Lying down made things worse. The ear surgery created so much noise in my head I couldn't sit and concentrate. It sounded like a field of locusts, a sound that never goes away. It starts messing with your psyche and takes you completely out of your element."

Michael couldn't paint. As time mounted, the idea of trying to paint again scared him. "I was afraid to go into the studio. If it turned out I couldn't concentrate enough to paint, I'd have an added psychological battle to fight."

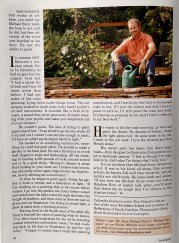

Michael needed to do something constructive, something he could feel good about. He decided to make a garden in his back yard. He and a friend put up a rock wall, flagstone steps, and landscaping. Hauling 4,000 pounds of rocks around broke out the sweat, and all that sweating turned out to be a good thing. "Meniere's disease is about fluid buildup in your inner ear. I believe that becoming physically active again helped lower my fluid levels, slowly allowing me to feel better."

In a sense, the garden saved him. In time, he began to paint again. Today, his garden serves as a retreat and a laboratory of light. "If I'm working on a painting that is two hours before sunset, I go into the garden two hours before sunset and watch how the light comes through the trees, the length of shadows, and their color as they are cast on grass and my flagstones. I'm trying to create light, a glow. It takes time, a layering process."

Having lived in the South most of his adult life, Michael's learned the value of painting what he knows. "I've often found inspiration for my art by traveling coastal waterways and interior vistas," he said. Looking back on his days in Charleston, Michael says he "got lucky." That's how he refers to having lived in Charleston. "I began to realize that I really like painting coastal areas, and I was lucky that that is what people want to buy. If I won the lottery and didn't have to paint to survive, I'd still paint the coast and water. It's become so personal for me that I feel it's reflected in my best work."

Dreams Of Sedona

Michael wants to hit the road someday, go out West, and paint the desert. He dreams of Sedona where the light glows red. "At some point in my life, I want to live out West. I love the Arizona and New Mexico areas."

Michael's career path has taken him down many roads - from designer to illustrator, from portrait artist to landscape painter. "I feel as though I've come full circle. And today I'm doing what I truly love."

It's no accident that Michael Story became an artist. It was in his blood all along. Like all true artists, he knows full well that creativity and adversity are old friends. Michael leans back and smiles. "If you ever see Michael Story come out with a Rainbow Row or basket lady print, you'll know that times are so tough that I've thrown in the creative towel."